Our assumed history is but a strange wind that

leaves no mark upon an indifferent sea.

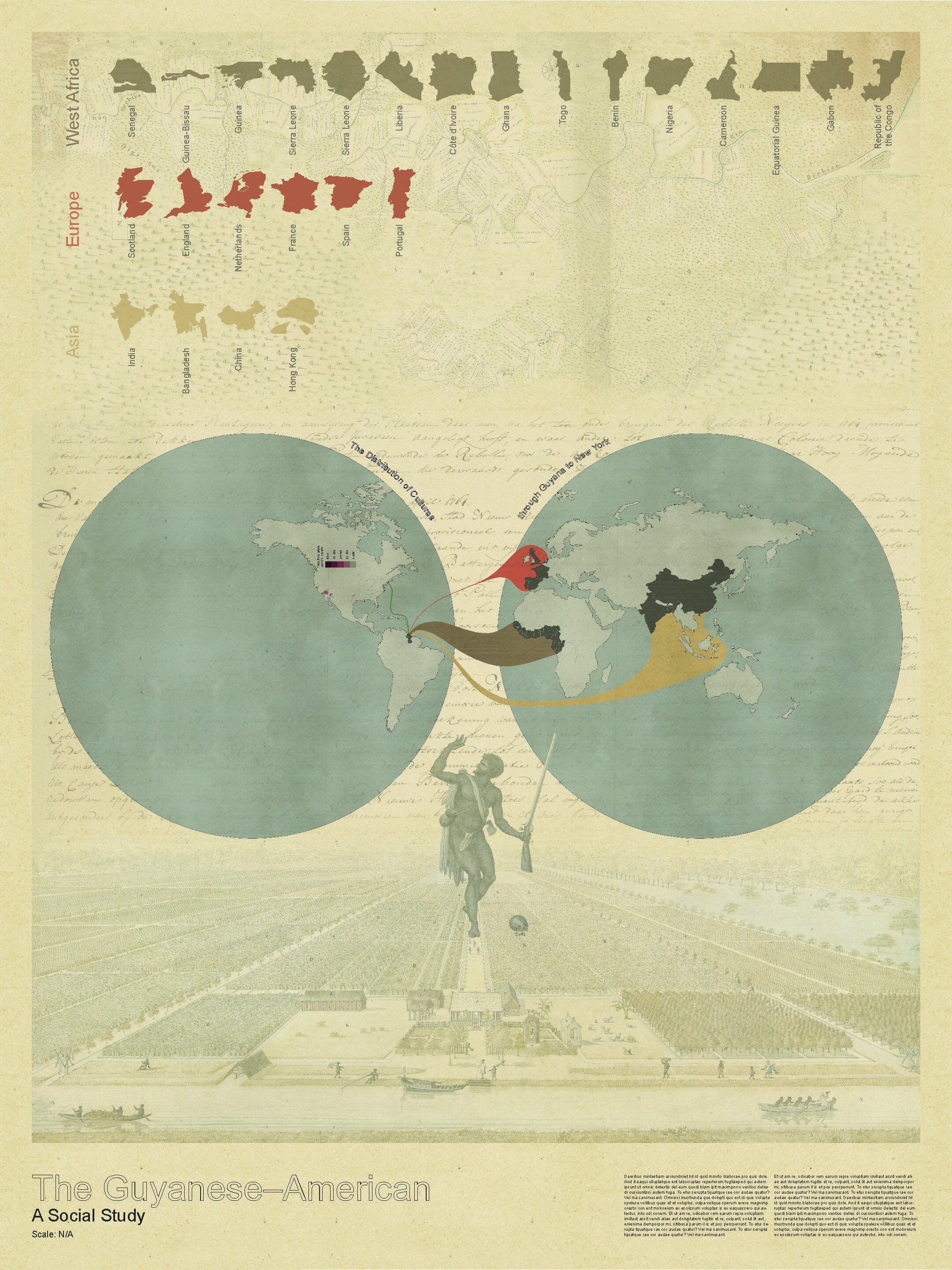

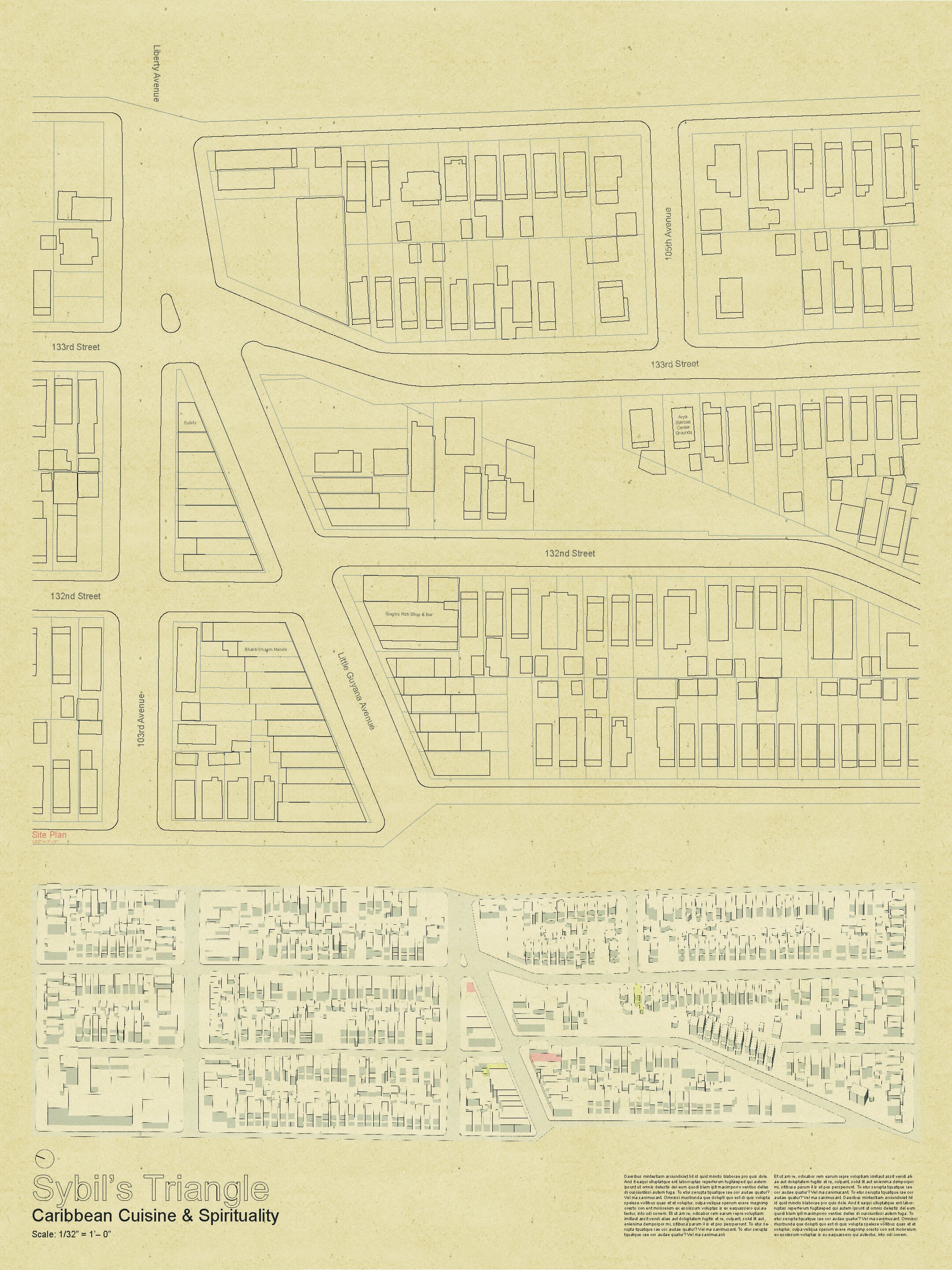

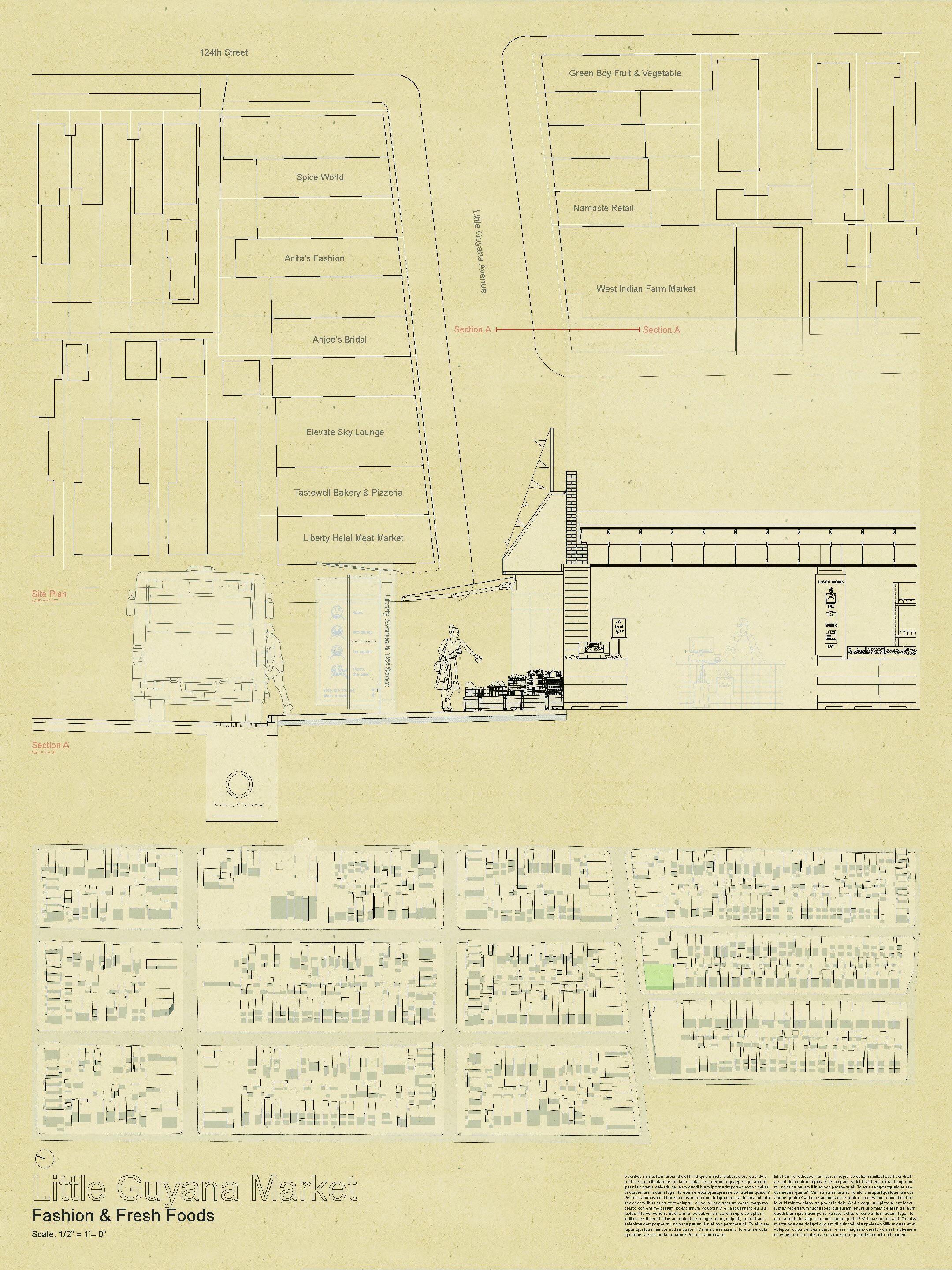

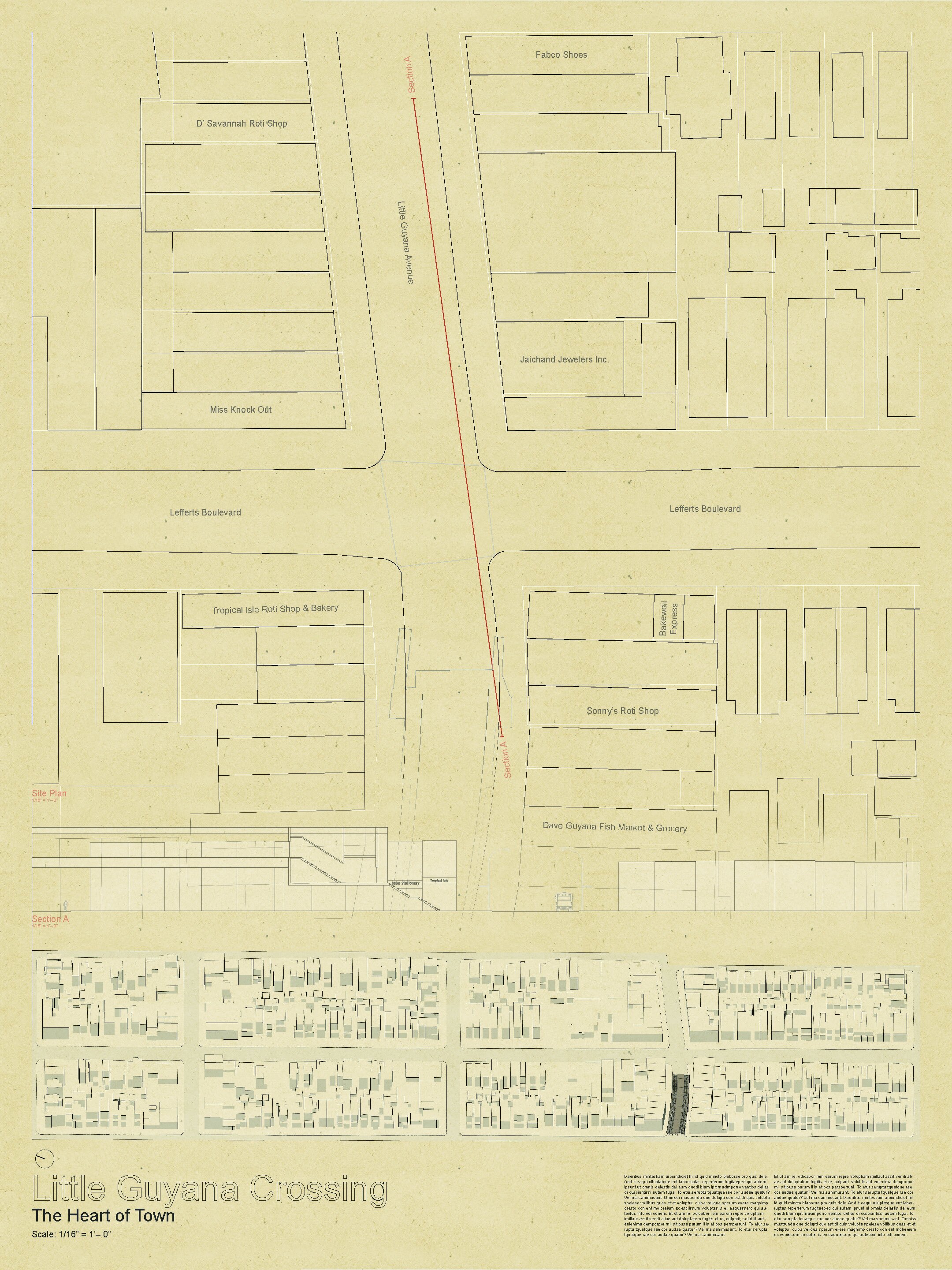

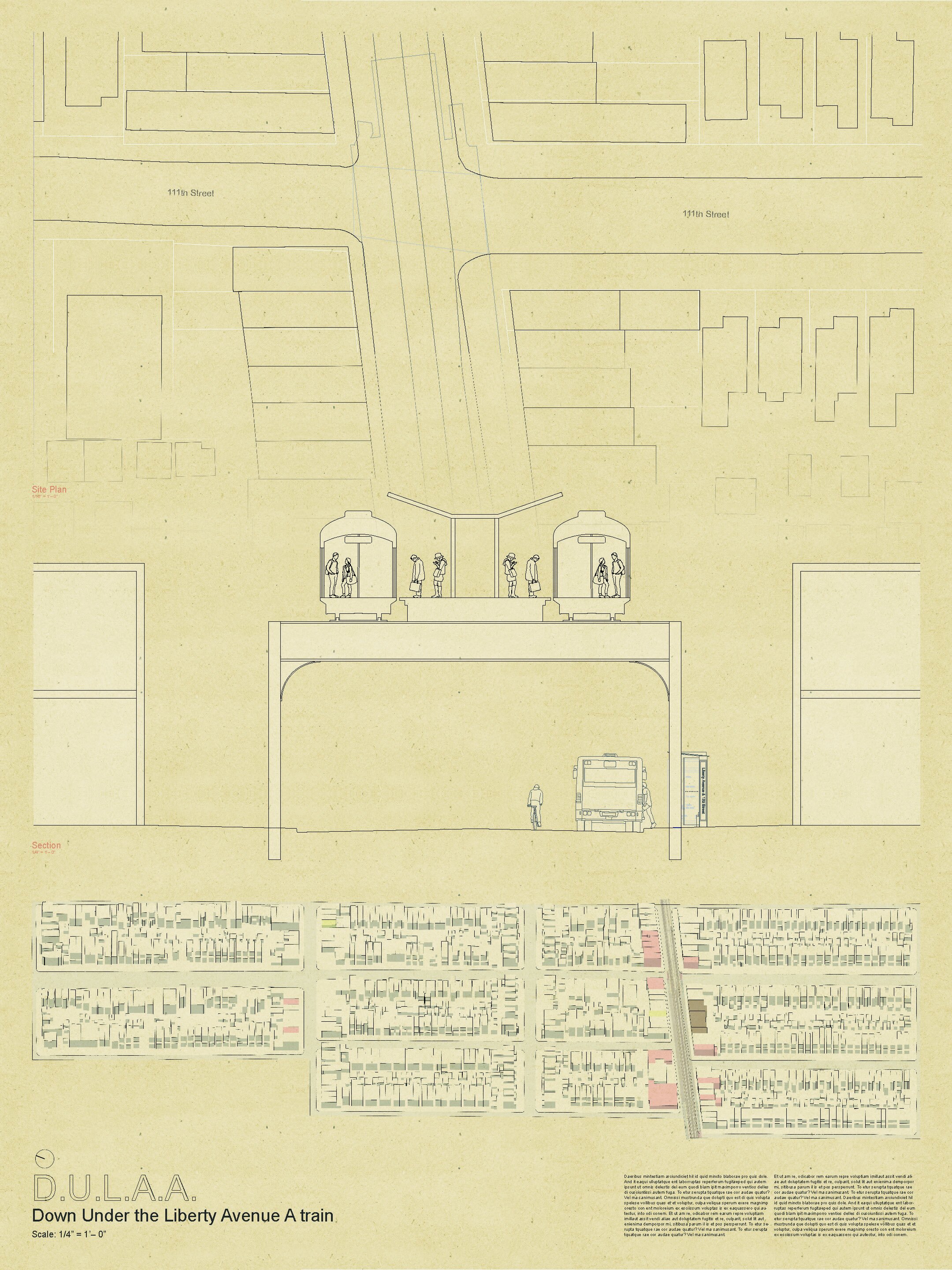

DESIGN X:

THE LITTLE GUYANA ARCHIVE.

Spring, 2022

PROJECT DETAILS:

ARCH 5902: Design X

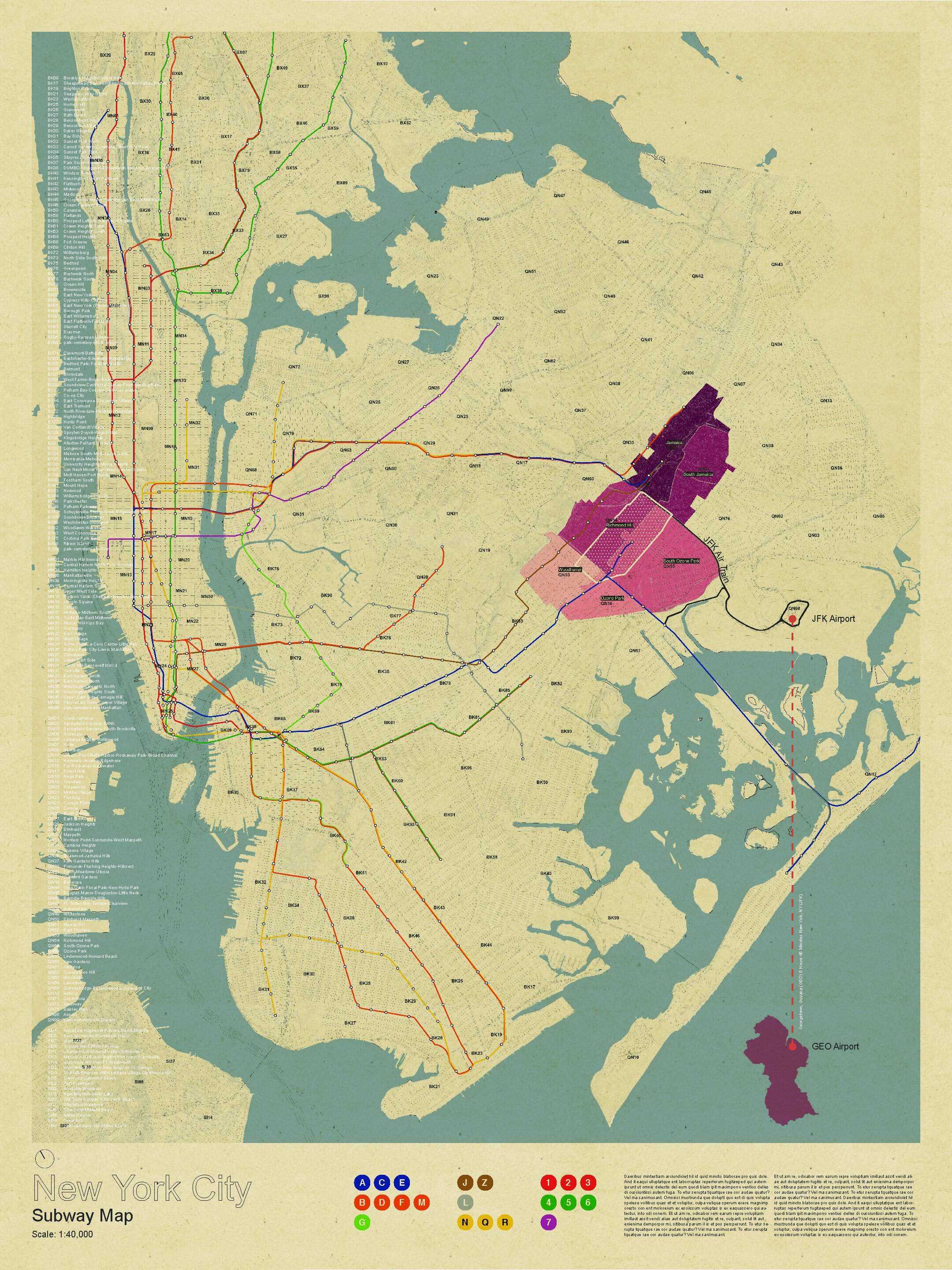

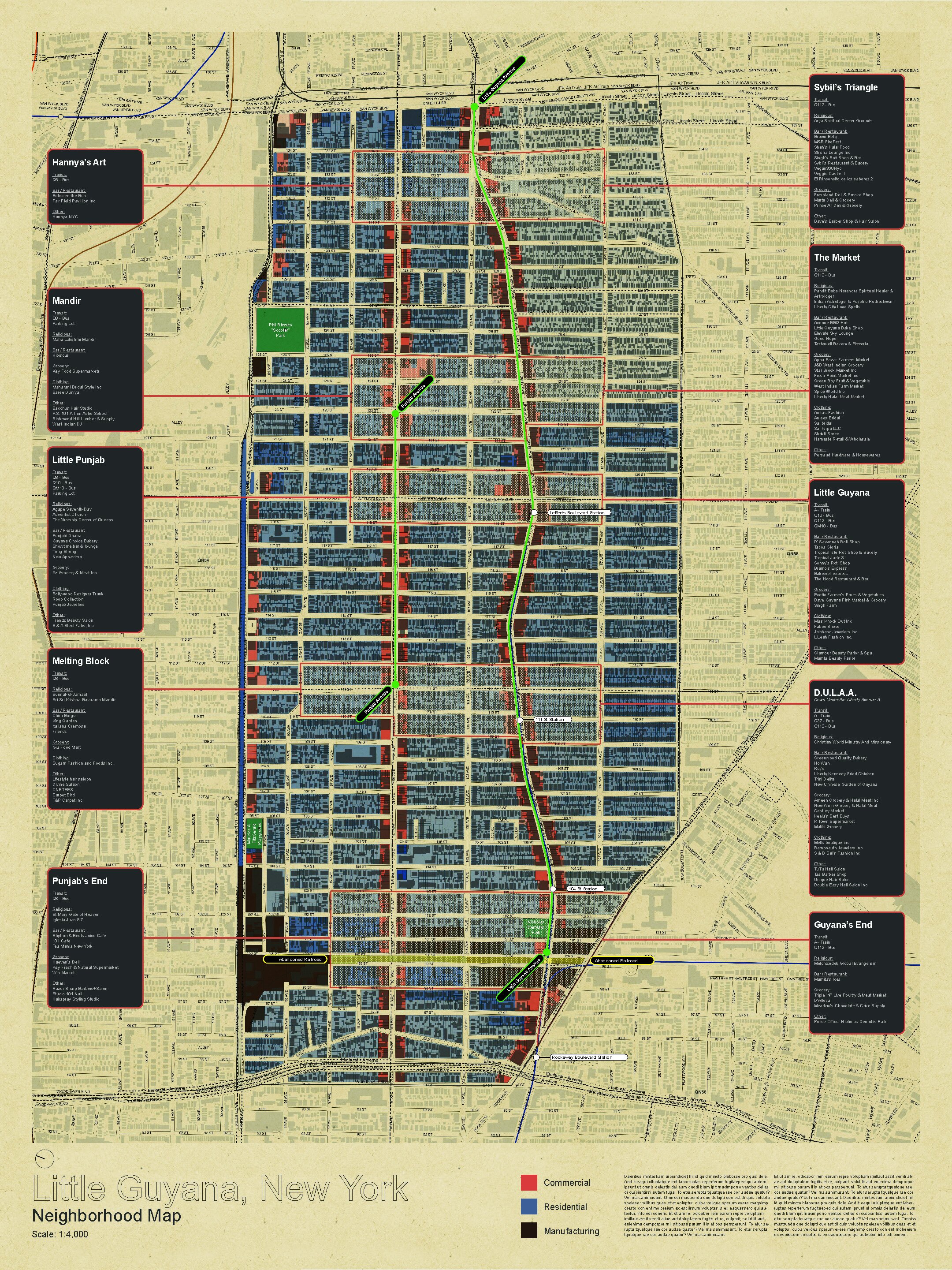

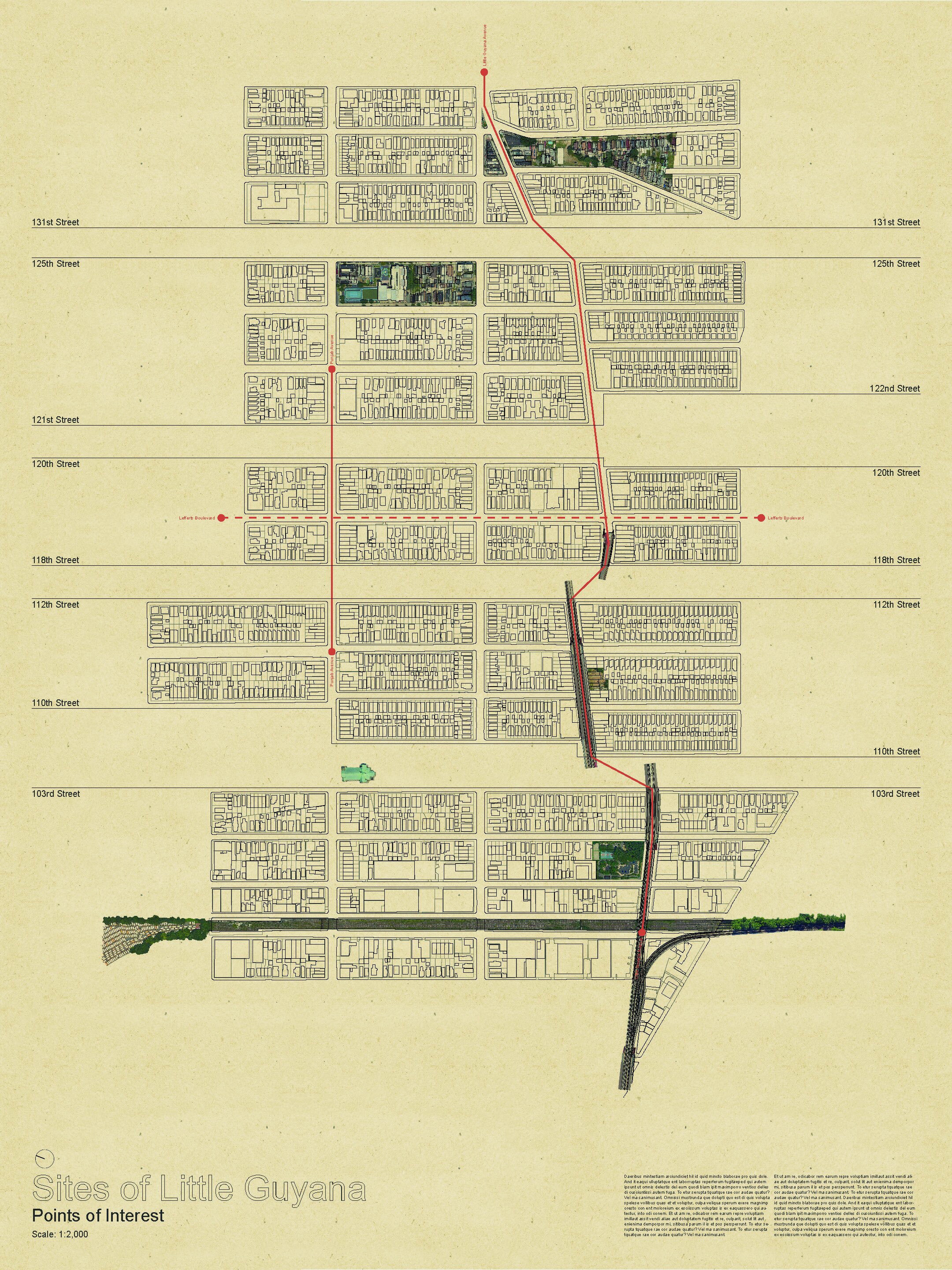

Richmond Hill, New York, USA

Tau DuFour

Emma Silverblatt

The Sankofa Bird

It is not taboo to fetch what is at risk of being left behind.

Akan. Gold Weight in Form of Sankofa Bird. Brass, 1 x 2 3/4 x 1 1/4 in. (2.5 x 7 x 3.2 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Carll H. de Silver Fund

Sankofa means “Go back and get it.” As the Akan proverb goes, “Se wo were fi na wosan kofa a yenkyiri.” To wit, it is not taboo to go back and get something after you have forgotten it. More literally, it means if you forget and you go back to get it, there is nothing wrong with it.

That history has much to teach is not in question but the wisdom of this sentiment is even more pronounced in societies which have nothing more than an oral tradition to transmit their culture and values. Then, not only is history important, but also those who know it. Further, the literary and narrative memorials the elders establish must be preserved lest their discoveries be lost forever.

The arrogance of succeeding generations may lead them to ignore established conventions and traditions because the events and experiences that led to their construction would have faded out of the general consciousness but this is a grave error that must be avoided. Sankofa embodies the spirit and attitude of reverence for the past, reverence for one’s forebears, reverence for one’s history, reverence for one’s elders. The mythical bird effortfully bending its neck to reach back for the abandoned but precious egg signifies the diligence and effort required to pay due reverence to the past and give it its proper place in the current scheme of events. Sankofa is a gentle admonition that if even in our arrogance we overlook the gems from the past, when we come to our senses we should be humble enough to retrace our steps and make amends. As the popular saying goes, those who do not know history are doomed to repeat it. So are those who do not know or respect their roots and history bound to repeat its flaws and mistakes.

About Me

My name is Jonathan Plass and I am a Guyanese-American artist, activist, and architect who was born in Brooklyn.

To learn more about me:

Resume

Why I Design

My father Edmond Plass was born in Guyana and immigrated to New York in 1978 and now does carpentry.

New Amsterdam, Berbice, Guyana

My mother Barbara Schweizer was born in New York to family that fled from Czechoslovakia following WWII.

Ober-Johnsdorf, Pardubicky kraja, Czechoslovakia

The Data of Diaspora

The majority of Guyanese immigrants, some 140,000, live in New York City making them the fifth-largest foreign-born population in New York.

BlackSpace Urbanist Collective, Inc.

I demand a present and future where people of color, spaces of color, and

cultures of color matter and thrive.

While what one does is very important, the way one does is also critical. Acknowledging past oppressions, triumphs, future aspirations, and challenges, BlackSpace Urbanist Collective created this manifesto to guide their growth as a group and their interactions with partners and communities. I seek to employee these principles while connecting with the community of Little Guyana.

Create circles, not lines

Create less hierarchy and more dialogue, inclusion, and empowerment.

Choose critical connections over critical mass

Quality over quantity. Focus on creating critical and authentic relationships to support mutual adaptation and evolution over time.

Move at the speed of trust

Grow trust and move together with fluidity at whatever speed is necessary.

Be humble learners who practice deep listening

Listen deeply and approach the work with an attitude towards learning, without assumptions and predetermined solutions. Take criticism without dispute.

Celebrate, catalyze, and amplify black joy

Black joy is a radical act. Give due space to joy, laughter, humor, and gratitude.

Plan with, design with

Walk with people as they imagine and realize their own futures. Be connectors, conveners, and collaborators—not representatives.

Center lived experience

Lived experience is an important expertise; center it so it can be a guide and touchstone of all work.

Seek people at the margins

Acknowledge the structures that create, maintain and uphold inequity. Learn and practice new ways of intentionally making space for marginalized voices, stories, and bodies.

Reckon with the past to build the future

Meaningfully acknowledge the histories, injustice, innovations, and victories of spaces and places before new work begins. Reckon with the past as a means of healing, building trust, and deepening understanding of self and others.

Protect & strengthen culture

Make visible and strengthen Black cultures and spaces to honor their sacredness and prevent their erasure. Amplify and support Black assets of all forms—from leaders, institutions, and businesses to arts, culture, and histories.

Cultivate wealth

Cultivate a wealth of time, talent, and treasure that provide the freedom to risk, fail, learn, and grow.

Foster personal & communal evolution

Make opportunities to expand leadership and capacity.

Promote excellence

Amplify, elevate, and love Black vanguards and the variety of their challenging, creative, exceptional, and innovative work and spaces. Allow excellence to build influence that creates opportunities for present and future generations.

Manifest the future

Black people, Black culture, and Black spaces exist in the future! Imagine and design the future into existence now, working inside and outside of social and political systems.

The Exhibit of American Negroes

The problem of the twentieth century is the problem of the color-line.

— W. E. B. Du Bois

I seek to follow in the footsteps of those before me and preform a contemporary social study based on W. E. B. Du Bois study for The Exhibit of American Negroes in 1900.

The first set of infographics created for the American Negro Exhibit was part of Du Boi’s The Georgia Negro: A Social Study, the study he prepared specifically for the Exposition Universelle at the request of Calloway. Representing the largest black population in any US state, Du Bois and his team used Georgia’s diverse and growing black population as a case study to demonstrate the progress made by African Americans since the Civil War. In addition to holding up Atlanta University’s home state as representative of black populations across the country, Du Bois and his team were interested in establishing the Black South’s place within and claim to global modernity.

The cross-fertilization of visual art and social sciences here marks an important transitional moment in the history of the disciplines while offering alternative visions of how social scientific data might be made more accessible to the populations and people from whom such data is collected. In opposition to the deeply allegorical and intentionally convoluted language that Du Bois deployed in his writings to convey the structures of oppression, alienation, and isolation under Jim Crow segregation—or what Du Bois termed “life within the Veil”—here Du Bois and his design team used clean lines, bright color, and a sparse style to visually convey the American color line to a European audience. This stylistic decision opens up questions about the aesthetics of the color line. This focus on modernist design, as well as the diasporic sensibilities of the images, further points to Du Bois’s interesting in representing the Black South as an integral part of modernity, a “small nation of people” who shared more in common with the broader, future-oriented “thinking world” than with an insular, backward-looking United States, where Jim Crow segregation was the rule of the land.

The Reductive Remnants of Redlining

Among the thousands of area descriptions created by agents of the federal government's Home Owners' Loan Corporation between 1935 and 1940. HOLC staff members, using data and evaluations organized by local real estate professionals—lenders, developers, and real estate appraisers—in each city, assigned grades to residential neighborhoods that reflected their "mortgage security" that would then be visualized on color-coded maps. Neighborhoods receiving the highest grade of "A"—colored green on the maps—were deemed minimal risks for banks and other mortgage lenders when they were determining who should received loans and which areas in the city were safe investments. Those receiving the lowest grade of "D," colored red, were considered "hazardous."

These grades were a tool for redlining: making it difficult or impossible for people in certain areas to access mortgage financing and thus become homeowners. Redlining directed both public and private capital to native-born white families and away from African American and immigrant families. As homeownership was arguably the most significant means of intergenerational wealth building in the United States in the twentieth century, these redlining practices from eight decades ago had long-term effects in creating wealth inequalities that we still see today. Mapping Inequality, we hope, will allow and encourage you to grapple with this history of government policies contributing to inequality.

Rewinding in Richmond Hill

“Wide streets with beautiful trees giving them shade and coolness, and, last but not least, a community of real homes where the tired city worker can find the rest he needs.”

—Richmond Hill Record, 1913 (Lefferts & Little Guyana Ave)

Brownsville Heritage House

An educational and cultural center for young and old, which spark individual and community achievements by focusing on a common heritage.

Mother Gaston, as she was affectionately known, realized early on that the one element missing in our community was the knowledge of our culture. She decided to do something about it. In 1969 she started the Children's Cultural Corner out of her home, where she taught young minds about their culture and history. This laid the foundation for BHH.

The Brownsville Heritage House provides cultural and educational programs for the community through the collection, study, exhibition and dissemination of historical artifacts relating to African American and other ethnic cultures. Plan and execute programs through art, poetry, drama, music, literature and audio/visual creative works to stimulate intergenerational contact between the youth and elder populations. Become the art and cultural epic center of Brooklyn that bridges the gap between the past, present, and future for all humanities to enjoy and embrace.

Located in Brownsville Brooklyn one can find a hidden treasure on the second floor of the historic first children's library built in 1914 by Andrew Carnegie for the Stone Avenue Branch (Formerly the Brownville Children's Library) of the Brooklyn Public Library. Brownsville Heritage House functions as a Multi-Cultural Center that focus on the arts,culture, education and history. Here you will find ongoing exhibits featuring historical figures, local artists, sculptures and photo collages depicting Brownsville and surrounding communities.

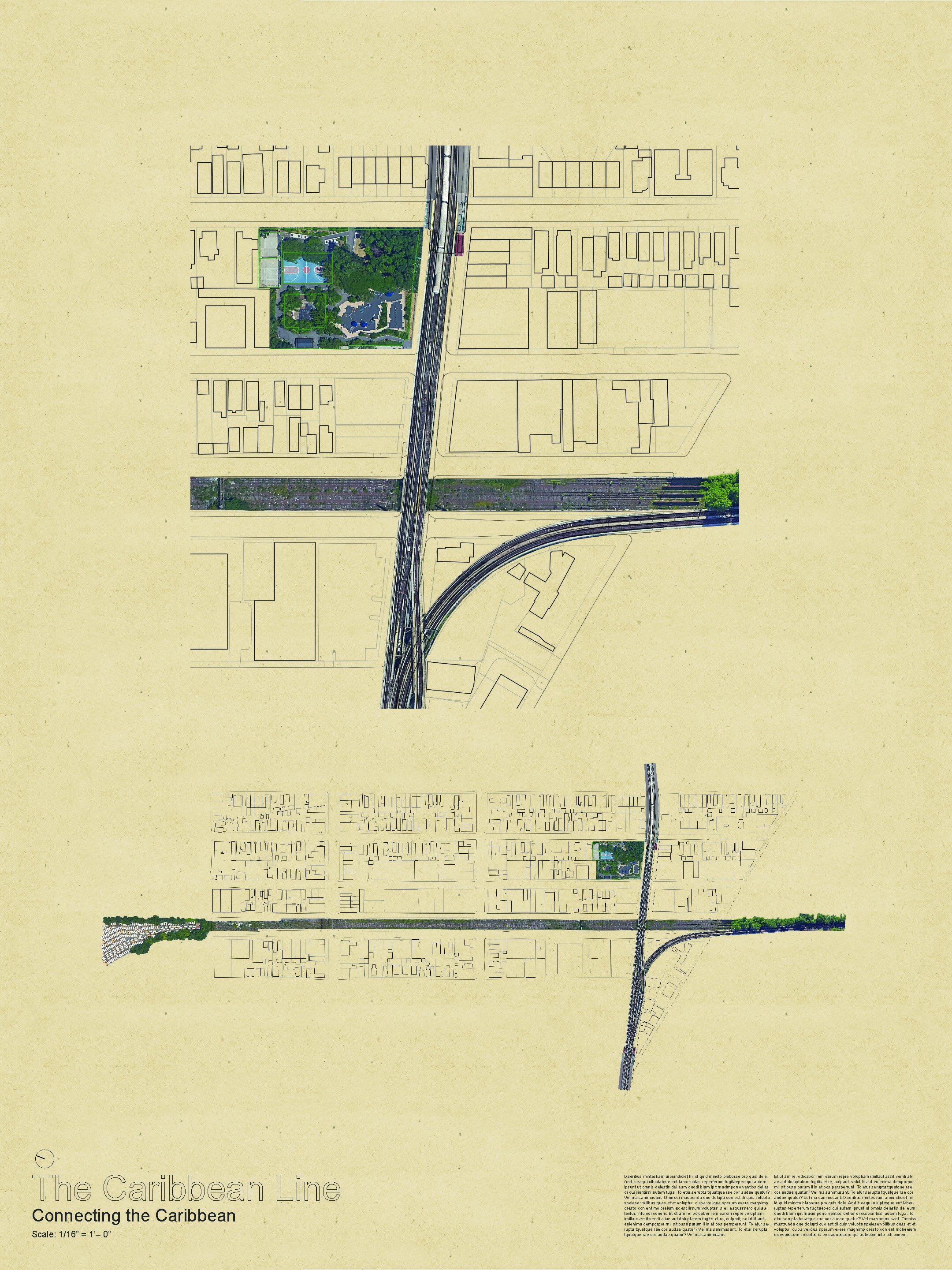

The Queens Link Proposal

The QueensLink looks to provide a new north-south transit link in Queens while also using available land for new park space.

The QueensLink proposes rerouting the M train south after 63rd Dr-Rego Park station along a new 3.5-mile extension south along the border of Rego Park and Forest Hills, the through Forest Park, Woodhaven, and Ozone Park before connecting to the existing A train to Rockaway Park.

The M would be routed to Rockaway Park, eliminating the current shuttle service and doubling overall service to the Rockaways. With the M no longer running to Forest Hills the G could be extended in its place, having been cut back to Court Sq in 2001. Proposals in the past have looked at reactivating rail on the line but have faced opposition due to the perceived negative impacts trains would have on nearby homes. An idea was floated in 2015 to convert the right of way into a High Line style park, but this too went nowhere because it would have prevented any future use for transit. Both new park space and transit options in Queens; this shouldn’t be an either-or situation. So we took a look at the right of way again and tried to figure out a way for both parks and transit to coexist. The QueensLink was born.

B. Arch Thesis Interim Review Exhibition

Milstein Hall, Ithaca, NY

3/23/2022